According to the INFORM Risk Index that assesses and ranks the risks of humanitarian crises and disasters, Türkiye falls into the high-risk category with a score of 5, placing it 45th out of 191 countries. While Türkiye is renowned for her many natural and cultural jewels, she faces significant threats from disasters that could potentially endanger these national treasures. Indeed, the Türkiye–Syria earthquakes of 6 February and other disasters throughout the year highlighted Türkiye’s vulnerability.

The Türkiye–Syria earthquakes had repercussions fare beyond the immediate disaster zone. This disaster engulfed the entire combined population of the two aforementioned countries as they rushed to the aid of their embattled and traumatized compatriots. Indeed, the aftermath of the catastrophe demonstrated how important risk mitigation and disaster preparedness is in reducing the negative effects of disasters.

The inevitability of natural disasters underscores the critical importance of pre-disaster preparedness and planning. Instead of focusing on how to respond once a disaster has struck, we should ask ourselves what preemptive measures can be taken before they do occur. While disasters will invariably cause damage and losses of life, it is possible to minimize these tragic outcomes by investing in disaster preparedness and risk mitigation. Nevertheless, this is not a task that individual organizations can undertake on their own. Since an informed society is one of the most important factors in reducing risks, awareness-building efforts are of critical importance, especially for a country like Türkiye whose vulnerability profile places her at high risk. Given this, the Turkish Red Crescent (TRC) takes its responsibility of raising awareness among society very seriously.

The Türkiye–Syria earthquakes struck Pazarcık and Elbistan—two districts in Türkiye’s southeastern province of Kahramanmaraş—on 6 February 2023. As both quakes registered greater than Mw 7, millions of people across eleven provinces in Türkiye, and many more in neighboring Syria, were either directly or indirectly affected. As with every disaster, TRC is adequately equipped to implement state-of-the-art disaster response strategies or mount swift responses through its extensive, highly organized network of volunteers and resources located throughout Türkiye’s eighty-one provinces. The earthquakes on this fateful day were no exception, as they brought out the TRC’s full potential. TRC coordinated with its various partners to provide millions of meals both to those affected by the disaster and the teams involved in rescue efforts.

TRC designed its systems to consolidate all of its production and distribution operations under a single roof, thereby minimizing the risk of anything falling through the cracks during a disaster of such great magnitude. TRC also launched an AI-driven system that allowed both disaster victims and first responders to use WhatsApp to locate food distribution centers, shelters, and other essential venues. Beyond our primary role in food distribution, we provided shelter, psychosocial support, humanitarian relief, healthcare, logistics assistance, and warehouse management to ensure that no one was left behind.

Following the disaster’s immediate aftermath, TRC began making plans for medium- and long-term recovery, focusing initially on building container and tent cities for displaced communities. Thereafter, recovery efforts focused on developing medium- and long-term solutions. That said, however, we continued to see to the needs of displaced individuals even after they had moved into container and tent cities and, so as not to overlook rural communities, conducted regular visits to more of the remote areas to see to it that they were received the care and attention they needed.

TRC’s Activities on the Ground

TRC’s initial and subsequent efforts in the disaster area include the following:

- Upon receiving information that an earthquake had struck, we shared what he had learned with domestic and international groups and verified its accuracy with local response centers.

- We conducted an impact analysis, disseminated information through our internal networks, and kept all relevant parties abreast of the events as they unfolded.

- The Director General of Disaster Management and Climate Change, the Deputy Minister of Interior, and various ministers arrived at the disaster site to coordinate all field operations locally.

- Instructions were issued for all tents and blankets stored in TRC warehouses to be delivered to the disaster zone. Warehouse statistics, quantities of tents and blankets at each location, contact persons and their badge numbers, and other relevant information were provided to AFAD.

- TRC General Managers were assigned to specific provinces within the disaster zone to oversee and coordinate field operations.

- Our branches in the disaster zone were redeployed to the hardest-hit areas, where they were directed to provincial AFAD centers so that they would be able to make full use of their local networking capacities.

- Disaster response teams from Adana, Gaziantep, and Osmaniye arrived and immediately commenced operations.

- Nearby TRC branches and Disaster Management Centers sent catering vehicles, mobile soup kitchens, and several of their staff members to the field.

- Disaster coordination and support teams were assigned tasks that aligned with their specific areas of responsibility.

- Primary response and logistics support centers were dispatched to the disaster zone in a well-coordinated manner.

- NGOs and organizations specializing in food and water distribution were mobilized and directed to the disaster zone.

- A level 4 incident command center was established and all relevant personnel were called to the disaster operations center.

- Personnel were assigned to man the AFAD crisis center established to coordinate response efforts.

- Communication groups were formed where they would be most effective.

- Reporting systems were set up, communication capacities were assessed, and communication equipment was delivered to places needing them.

- Once equipment for distributing food, water, and other essential goods was identified, logistics units were alerted to expedite their dispatch.

- Food and water distribution began at 5:00 a.m. in Gaziantep, 5:30 a.m. in Adana, 6:00 a.m. in Diyarbakır, 7:45 a.m. in Şanlıurfa, 8:30 a.m. in Malatya, 9:00 a.m. in Pazarcık, 10:00 a.m. in Iskenderun, 11:00 a.m. in Antakya, 5:30 in Kahramanmaraş, and 8:30 p.m. in Adıyaman.

- Registered volunteers were mobilized.

- A disaster request system was established to process and view incoming requests.

- A separate disaster incident command center was established in each individual disaster zone. These centers coordinated with members of the Nutrition Platform to ensure that food and water were distributed effectively.

- Catering vehicles were deployed to designated areas in the field.

- Aid campaigns were organized nationwide and logistics warehouses were established to distribute essential goods.

- The Directorate General of International Relations was tasked with coordinating international aid and contacts were made the IFRC.

- Fourteen team leaders were appointed and twenty-seven district representatives were appointed.

- Thirteen service units provided comprehensive psychosocial and healthcare services, conducted regular needs assessments, and launched specialized programs in six provinces. We conducted community-based responses and provided cash assistance to households in need.

- Individuals who shared their locations with TRC’s WhatsApp were directed to the nearest distribution centers.

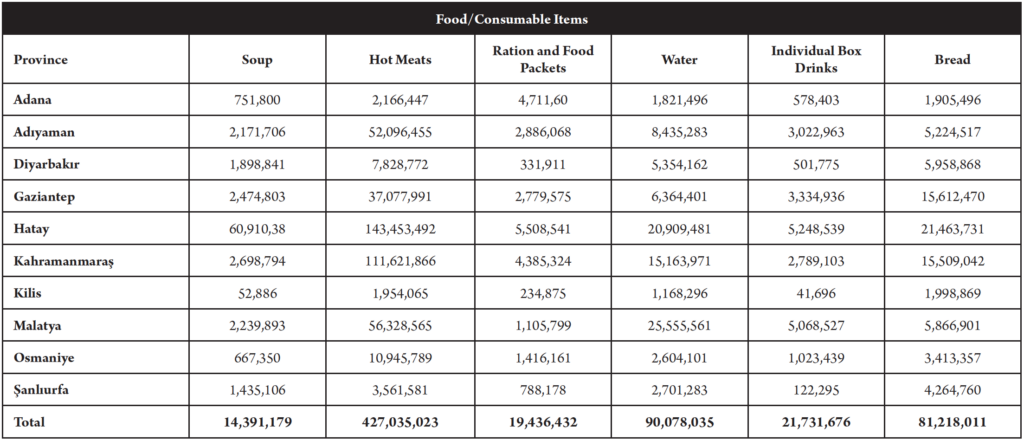

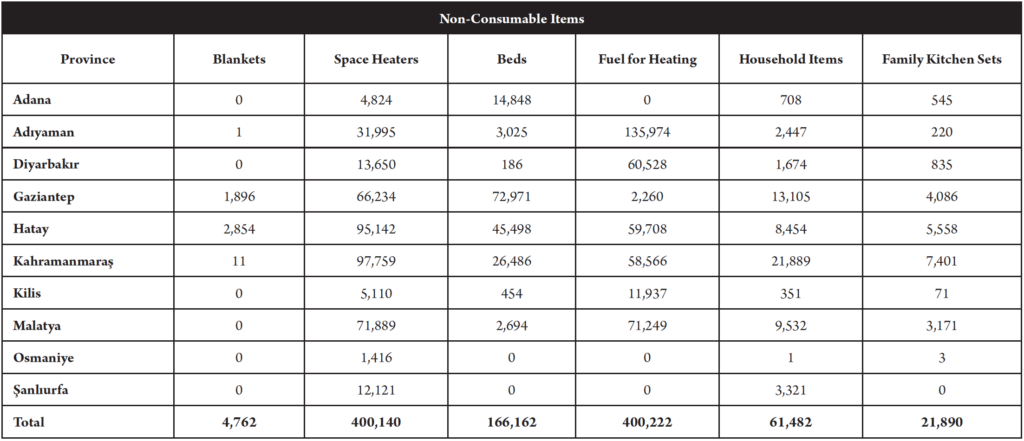

A total of 427,035,023 hot meals were served to earthquake victims and first responders following the Türkiye–Syria earthquakes (Table 1) and 1,054,648 aid items were distributed to affected communities (Table 2).

Table 1-Food/Consumable Items Distributed by Province

Table 2-Non-Consumable Items Distributed by Province

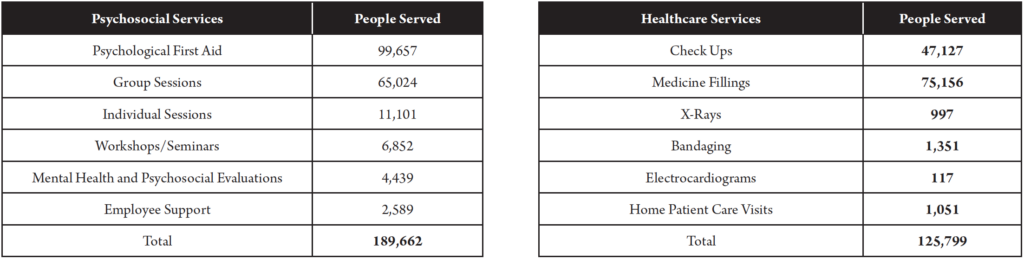

A total of 125,799 and 189,662 earthquake victims received healthcare and psychosocial services, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3-Pyschosocial and Healthcare Services

After the Türkiye–Syria earthquakes, a total of 2,487 professional staff members and 56,996 volunteers were active in the field. Together they contributed a total of 667,902 days’ worth of work (439,918 by staff and 227,984 by volunteers). Beyond this, a total of 71,044 people used the mobile showers and laundry services set up as part of water sanitation efforts.

Other Disasters in 2023

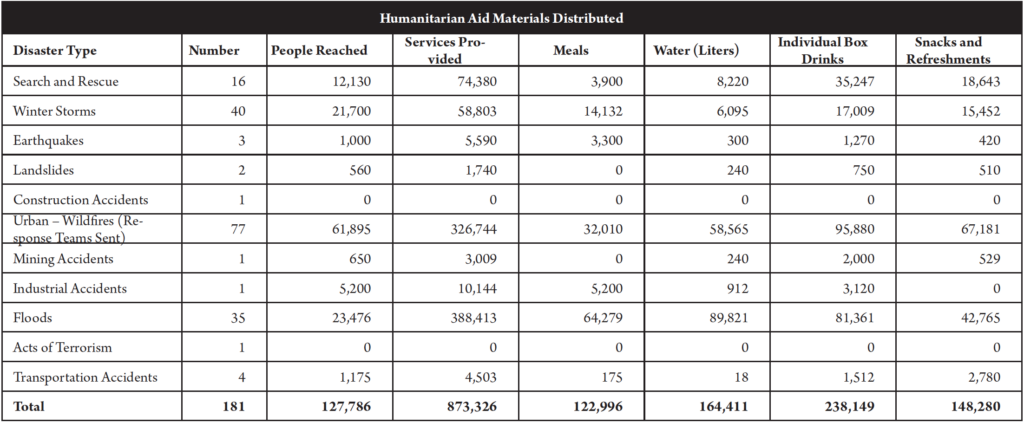

Table 4 lists the other disasters and emergency situations experienced in Türkiye in 2023.

Table 4-Disasters and Response Efforts in 2023 (Excluding Pazarcık)

TRC responded to a total of 181 individual disasters spanning eleven different disaster types. As part of these responses, TRC provided 127,786 individuals with different forms of relief, delivering a total of 873,326 services, reflecting the fact that many people received multiple forms of aid. The total amount of food and other consumable items distributed consisted of 122,996 meals, 164,411 liters of water, 238,149 individual box drinks, and 148,280 snacks and other refreshments.

While it is impossible to prevent certain types of disasters (e.g., earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunamis) from occurring, we can—and indeed must—do whatever is in our power to prevent human- and climate-induced disasters take all the necessary precautions to minimize the long-term effects and damage they inflict on society.

By focusing strictly on human-centric goals, we risk missing the broader picture. Just like individual human beings need protection from external factors, cities must themselves be designed to withstand disasters. Constructing disaster-resilient cities will lead to less destruction, fewer casualties, reduced property loss, and a mitigated impact on national economies.

1 INFORM (2024). Inform Risk Index. https://drmkc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/inform-index/INFORM-Risk/Results-and-data/moduleId/1782/id/469/controller/Admin/action/Results#inline-nav-1