On 6 February 2023, as preparations for the Republic’s centennial anniversary were in the top gear across Türkiye’s vast geographical landscape, two successive earthquakes plunged the country into another direction, another air – an atmosphere where preparations for a landmark centenary celebration was forced to take a back seat in the social, cultural, and or historical consciousness of the people. These earthquakes originated in the districts of Pazarcık and Elbistan in Türkiye’s southeastern province of Kahramanmaraş. Not only was the entire country shaken to its core, the earthquakes (emanating from the East Anatolian Fault Zone), wrought extensive destruction both in eighteen of Türkiye’s own provinces and across the border in Syria; the aftermath of the earthquakes would later go on to have far reaching and enduring repercussions on the nation’s collective psyche. To paint a vivid picture of the scale of devastation would require an animated yet conscious and ethical comparisons with previous earthquakes in Türkiye. To that end, in terms of loss of life and property damage; the 2023 Türkiye–Syria earthquakes surpass the 1939 Erzincan and 1999 Izmit earthquakes, becoming the most destructive disaster in the Republic’s 100-year history. Given the extensive impact of the earthquakes, conducting thorough assessments either commissioned by government agencies or individual researchers is likely to extend well into the future. In this article, written eleven months after the calamitous event, I will briefly assess, whilst drawing from the latest available data sourced primarily from official channels, how Turkish cities have responded to disasters. Additionally, I will offer my own insights into what measures need to be implemented to mitigate the detrimental effects of earthquake and other catastrophic events threatening Türkiye’s wider geographical landscape.

The 2023 Türkiye -Syria Earthquakes: A Disaster Greater than the 1999 Izmit Earthquake

On 6 February 2023, just before the dawn, while many were still fast asleep, an earthquake of Mw7.7 (focal depth = 8.6 km) struck Pazarcık –a district in Türkiye’s southeastern province of Kahramanmaraş –at 4:17 a.m. local time (UTC+03:00). Nine hours later at 3:24 p.m., a second earthquake of Mw7.6 (focal depth = 7 km) struck the district of Elbistan in the same province of Kahramanmaraş. If earthquakes were to speak a language and we were lettered and fluent in that spoken word; perhaps we might have heard it say: “I’m just not done yet,” because three weeks later on 20 February, another earthquake rattled the district of Yayladağı in the nearby province of Hatay at 8:04 p.m. These events, collectively referred to as the 2023 Türkiye–Syria Earthquakes, are but part of the greater history of seismic activity in Türkiye. It is critical to emphasize that out of the 269 earthquakes known to have caused loss of life or property in Türkiye since 1900, twenty of these earthquakes registered at magnitudes greater than 7 on the Richter scale. Of these twenty, the three most destructive in terms of fatalities as earlier mentioned are: the 2023 Türkiye -Syria earthquakes (50,783 deaths), the 1939 Erzincan earthquake (32,962 deaths), and the 1999 Izmit earthquake (17,479 deaths).

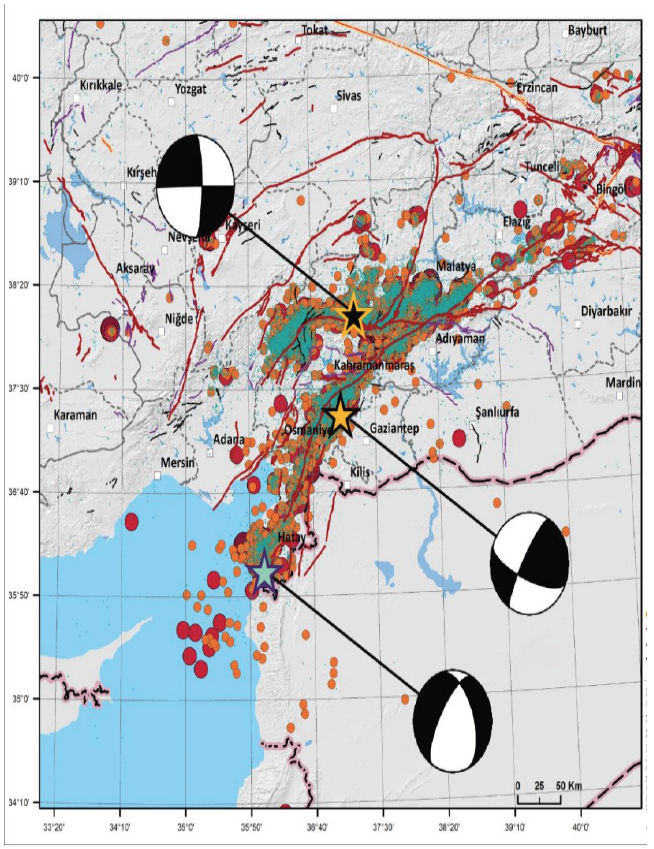

Figure 1 shows the three most destructive earthquakes, their magnitudes, and the geographical distributions of their aftershocks until 6 May of the same year. In the wake of the 2023 Türkiye -Syria earthquakes, preliminary reports estimating the amount of damage and economic cost of the earthquakes were prepared as expeditiously as possible. This expedited assessment and survey focused solely on the eleven provinces officially declared as disaster zones. However, when updated data revealed that eighteen provinces had in fact suffered damage, it became clear that the figures cited in these preliminary reports had underestimated the extent of the losses incurred. It was due to the updated figures that more provinces were declared disaster zones and thus in a state of emergency. This state of emergency was declared in the provinces of Kahramanmaraş, Hatay, Gaziantep, Malatya, Diyarbakır, Kilis, Şanlıurfa, Adıyaman, Osmaniye, Adana, and Elazığ after which the provinces of Bingöl, Kayseri, Mardin, Tunceli, Niğde, and Batman were added. Utilizing 2022 TÜİK demographic data preliminary reports recorded that 14,013,196 people across eleven provinces were directly affected by the earthquakes, including at least 1,738,035 migrants who were residing in the earthquake zone under temporary protection status at the time of the disaster.

In its March 2023 report, drawing on data from the eleven provinces initially declared disaster zones, Türkiye’s Presidency of Strategy and Budget concluded that the earthquake impacted Türkiye’s economy in many ways. Prominent among these was (1) the damage to housing which at 54.9% (1,073.9 billion TRY/56.9 billion USD), comprised the largest proportion of the economic impact incurred by Türkiye’s economy, (2) the damage to public infrastructure and service buildings, calculated at 242.5 billion TRY/12.9 billion USD, and (3) damage to the private sector (excluding housing) – specifically the manufacturing industry, energy, telecommunications, tourism, the health and education sectors, small businesses, and places of worship – totaled 222.4 billion TRY/11.8 billion USD. In terms of the macroeconomic impact of the earthquake, losses sustained by the insurance sector and of lost wages amounts to about 2 trillion TRY/103.6 billion USD. In lieu of the burden these losses imposed on the economy, the Presidency of Strategy and Budget has stated that the total economic impact could amount to approximately nine percent of the national income for the year 2023.

Figure 1: February 6 and February 20 earthquakes epicenters and aftershocks 5

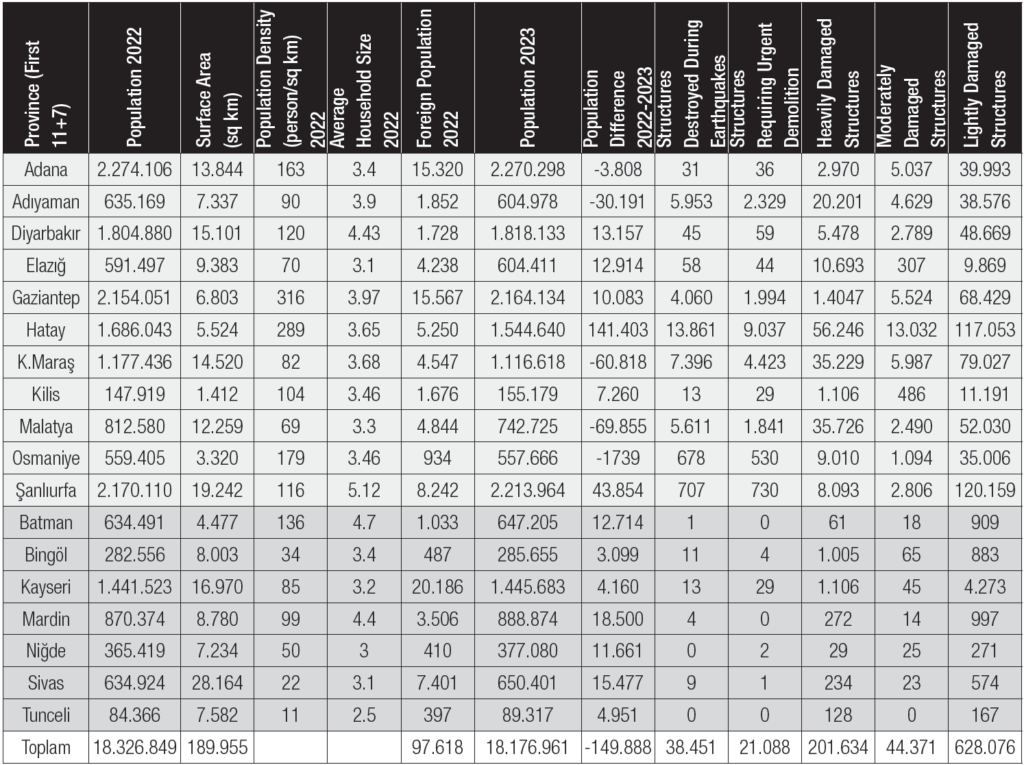

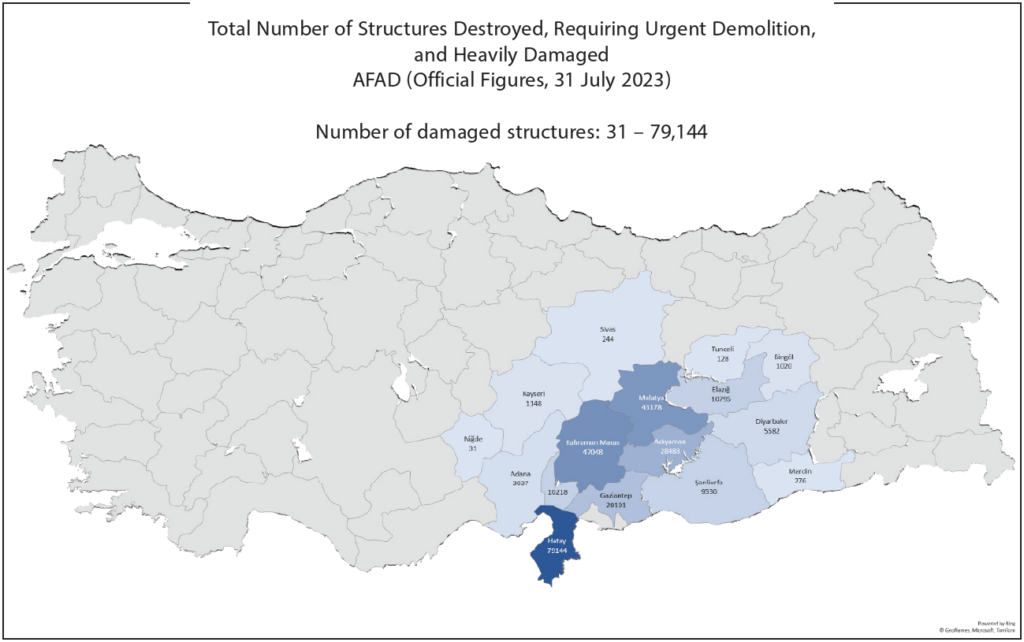

After completing the appeals process in the earthquake-affected provinces, analysis of the damage assessments and population findings revealed that over 190,000 km2 and 18 million inhabitants were affected, with approximately 260,000 structures either severely damaged or destroyed (see Figure 1 and Table 1). In Figure 2, the provinces of Hatay, Kahramanmaraş, Malatya, and Adıyaman suffered the greatest amount of structural damage. To ascertain the estimated amount of people impacted by the earthquake – on the one hand, an address-based population data for eighteen provinces from 2022 were used. On the second hand, 2023 population data published on 6 February 2024 (exactly one year after the initial earthquakes) provided insight into the number of individuals who had died or were displaced.

Table 1: Affected Population (2022 and 2023) and Structural Damage by Province

Figure 2 : Number of damaged structures in earthquake-affected provinces (total number of collapsed, urgently demolished, and heavily damaged structures

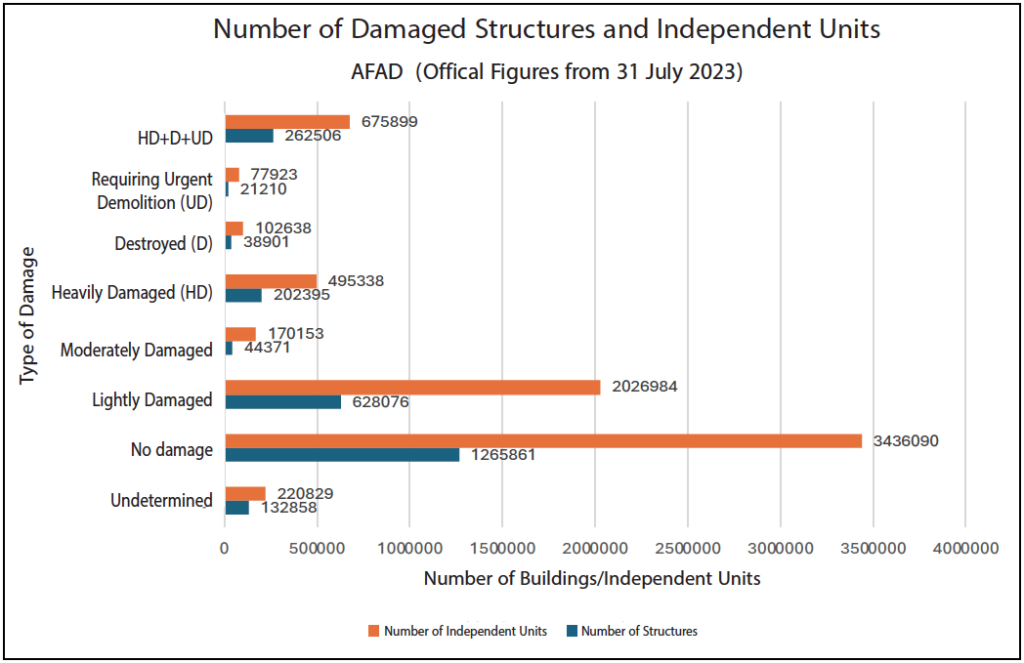

Figure 2 illustrates the number of damaged buildings and independent units in the eighteen provinces affected by the earthquakes, as documented in the damage assessment studies conducted by Türkiye’s Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change. Considering, however, that many structures also sustained light or moderate damage (see Table 1), the total number of structures affected is indeed higher than what is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 3: Number of Damaged Structures and Individual Units in the 18 Earthquake-Affected Provinces

At the risk of continuously rehashing the documented impact of the earthquake, it is important to reecho that it affected a considerably large geographical area. Geologists offered a persuasive explanation as to why this was the case. They acknowledge that the occurrence of earthquakes in the same region within a nine-hour interval contributed to the disaster’s magnitude. In the same breath, they pointed out that certain maximum acceleration values recorded in the area exceeded those projected in Türkiye’s seismic hazard map. Besides the lapses in projections, the civil engineers noted that non-compliance to prevailing building codes was largely responsible for the severe damage incurred.

In other words, the extensive destruction wrought by these earthquakes revealed two crucial truths that would have otherwise gone overlooked. Firstly, it dispelled Türkiye’s presumption that, despite numerous legal and administrative reforms enacted in the aftermath of the 1999 earthquake, the country was adequately prepared to deal with seismic disasters. Secondly, it demonstrated the country’s failure to capitalize on the lessons learned over the past twenty-five years and synthesize them into robust policy and comprehensive governance. In fact, it would be no be out of place to assert that such a catastrophic event with regional ramifications of such great magnitude was foreseeable prior to the 6 February earthquakes. This sentiment is evidence-based as research had suggested, based on historical data, that the presence of a seismic gap along the Eastern Anatolian Fault indicates the elevated possibility of a major earthquake in the near future. Consequently, Kahramanmaraş was designated as the pilot province to implement the Provincial Risk Reduction Plan (İl Afet Risk Azaltma Planı [henceforth IRAP]) initiated in 2019, thereby leading to the first IRAP being developed in this province. Despite the implementation of IRAP, no one anticipated a scenario wherein eighteen provinces would simultaneously be brought to their knees by a disaster of such magnitude. Not only did transportation, electrical, and natural gas infrastructure suffer a complete collapse, facilities critical in facilitating emergency responses, such as hospitals and airports, were rendered largely unusable. The sheer scale of destruction and the severity of the calamity left even Türkiye’s Disaster Response Plan (Türkiye Afet Müdahale Planı [henceforth TAMP]), revised in 2022, completely null and void, as it relied on emergency intervention by neighboring provinces.

What is more is that the earthquakes of 6 February revealed Türkiye’s responsiveness and capacity to promptly execute essential operations within the first seventy-two hours of a disaster to be inadequate, especially when coupled with inclement weather conditions and wide scale logistical collapse. These shortcomings adversely impacted the functionality of vital infrastructure, such as airports, intercity thoroughfares, and energy distribution networks. In light of the catastrophe that unfolded before the eyes of an entire nation, several recommendations can be made to minimize the loss of life and property when a future earthquake inevitably strikes: Plans to deal with worst-case scenarios need to be formulated for at the regional level; provinces outside the same fault zone, as opposed to neighboring provinces, should be selected to help provide material support and spearhead relief efforts in the event of a major earthquake; alternative transportation routes that factor in the influence of climatic conditions to allow for unfettered access to disaster-stricken areas need to be identified; and, most importantly, comprehensive preemptive studies and infrastructural projects need to be completed before earthquakes even strike. The events of 6 February and their aftermath offer invaluable lessons whilst sounding the alarm that a similar cataclysmic episode could occur should a major earthquake strike in or around the Sea of Marmara, thus providing an impetus to hasten the implementation of the above recommendations. Immediate revision and updating of IRAPs and, more importantly, TAMP are imperative to address the vulnerabilities exposed by the 6 February earthquakes. Therefore, urban areas at heightened risk of damage must likewise prioritize the implementation of risk-mitigation measures and establish robust budgetary and disciplinary mechanisms to ensure the adherence to and enforcement of these measures.

In drawing the curtains, it has to be noted that the creation of more resilient living spaces and the fostering of more resilient communities in cities that have suffered substantial damage from earthquakes should be of topmost priority for professionals engaged in disaster management. As a result, addressing a host of preemptive challenges that might arise in the wake of a disaster is essential for effective post-disaster urban planning. These include minimizing problems prevalent in temporary shelters, designing sustainable living environments in areas currently under construction, prioritizing the restoration of previous social ties in heavily damaged historic districts, improving connectivity between old and new urban areas with reliable public transportation services, and seamlessly integrating work and residential spaces.

1 AFAD (Afet ve Acil Durum Yönetimi Başkanlığı) tarafından açıklanan verilere göre, 6 Şubat 2023 tarihinde yerel saat ile 04.17’de ve 13.24’de merkez üssü Pazarcık (Kahramanmaraş) ve Elbistan (Kahramanmaraş) olan Mw 7.7 (8.6 km derinliğinde) ve Mw 7.6 (7.6 km derinliğinde) büyüklüğünde iki deprem meydana gelmiştir. Detaylı saha çalışmaları neticesinde, depremlerin sismolojik, geoteknik, yapısal ve sosyal etkilerini ODTÜ DMAM Ön Değerlendirme Raporu (22.02.2023) yaygın etkileri ilk bulgular olarak ortaya koymuştur.

2 Depremin doğrudan etkilediği açıklanan 11 il alfabetik sırayla şöyledir; Adana, Adıyaman, Diyarbakır, Elazığ, Gaziantep, Hatay, Kahramanmaraş, Kilis, Malatya, Osmaniye, Şanlıurfa. Ancak bu illere Haziran 2023 itibarıyla depremlerden etkilenen Batman, Bingöl, Kayseri, Mardin, Niğde, Sivas, Tunceli de eklenerek hasar gören il sayısı artmıştır (AFAD, 2023a).

3 Strateji Bütçe Başkanlığı. (2023, Mart) Kahramanmaraş ve Hatay Depremleri Raporu (https://www.sbb.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/2023-Kahramanmaras-ve-Hatay-Depremleri-Raporu.pdf )

4 Strateji Bütçe Başkanlığı. (2023, Mart) KahramanmaraşveHatayDepremleriRaporu (https://www.sbb.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/2023-Kahramanmaras- ve-Hatay-Depremleri-Raporu.pdf )

5 AFAD (2023a). 06 Şubat 2023 Pazarcık-Elbistan Kahramanmaraş(Mw:7.7–Mw:7.6) Depremleri Raporu, Deprem Dairesi Başkanlığı https://deprem.afad.gov.tr/assets/pdf/Kahramanmara%C5%9F%20Depremi%20%20Raporu_02.06.2023.pdf

6 ÇSB (2023), 1939 Erzincan Depremi, https://erzincan.csb.gov.tr/1939-erzincan-depremi-haber-16203

7 Özmen, B., (2000). 17 Ağustos 1999 İzmit Körfezi Depreminin Hasar Durumu (Rakamsal Verilerle), Türkiye Deprem Vakfı, https://deprem.gazi.edu.tr/posts/download?id=43388

8 Genel Hayata Etkili Afet Bölgesi İlanı. https://www.afad.gov.tr/genel-hayata-etkili-afet-bolgesi-hk

9 TÜİK. (2022). Adrese Dayalı Nüfus Sayımı, https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=49685

10 TÜİK. (2023). Adrese Dayalı Nüfus Sayımı, https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Adrese-Dayali-Nufus-Kayit-Sistemi-Sonuclari-2023-49684

11 AFAD. (2023b, Temmuz 31). AFAD Afet Yönetim Merkezi Daire Başkanlığı, Güncel Resmî Veri, Ankara.

12 NURLU, M. (2019). ‘Earthquake Activity in Turkey and Earthquake Risk Reduction Studies’ The Asian Conference on Disaster Reduction (ACDR 2019) organized by the Government of Turkey, the Government of Japan and Asian Disaster Reduction Center (ADRC), 25-27 November 2019, Ankara, Retrieved August 12, 2023, from https://www.adrc.asia/acdr/2019/documents/S2-02_ DeptEQ_AFAD.pdf.

13 ŞENOL BALABAN, M. (2019). Afete dirençli yerleşimler oluşturmak: Afet risklerini azaltma planı. Bilim ve Ütopya, cilt.25, sa.305, 29-34. https://bilimveutopya.com.tr/afete-direncli-yerlesimler-olusturmak-afet-risklerini-azaltma-plani

14 DMAM. (2023). https://eerc.metu.edu.tr/tr/system/files/documents/DMAM_2023_ Kahramanmaras-Pazarcik_ve_Elbistan_Depremleri_Raporu_TR_final.pdf