Türkiye’s topography is highly susceptible to natural disasters, which, compounded by emergent technological disasters, have resulted in profound human casualties and irrecoverable economic loss. As a result, national security and development initiatives have, since 2023, prioritized outcome- and impact-oriented, disaster-resilient urban-planning and community-building strategies to minimize human and material loss. Yet national and local task forces engaged in disaster risk and crisis management have unfortunately fallen short in implementing action plans aiming to mitigate and prevent risk. The deficiencies observed in post-disaster crisis management, interinstitutional coordination, risk management planning, and urbanization highlight the imperative to adopt an interdisciplinary, holistic, and comprehensive approach in addressing research problems. The year 2023 saw several ever-present hazards make the transition into full-blown disasters. These include forest fires in Türkiye’s southern and western coastal regions, flash flood in the country’s north, traffic accidents, CBRN incidents, and the Türkiye–Syria earthquakes of 6 February.

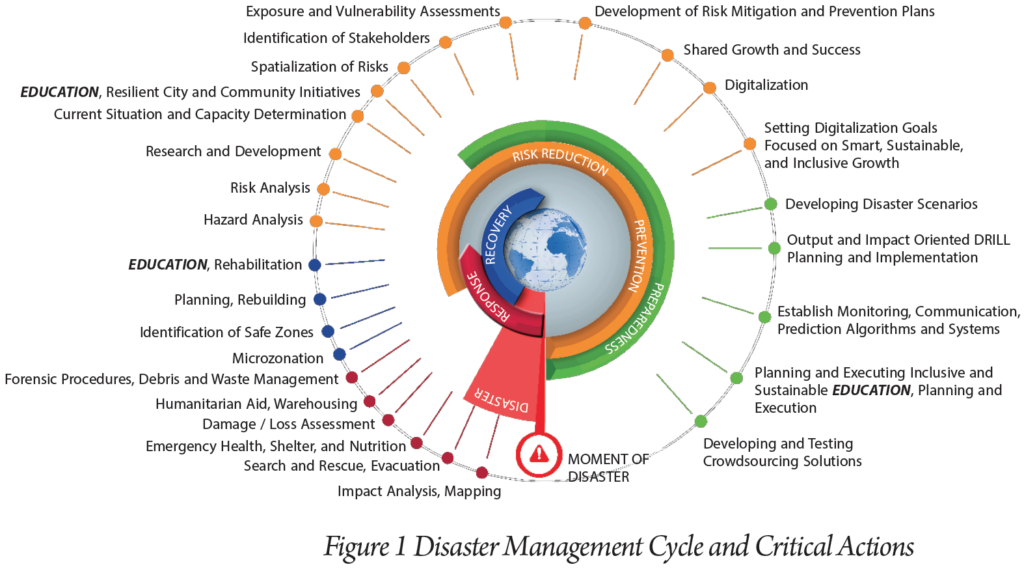

Disaster management is an ongoing, recurring process that demands continual refinement. It encompasses readiness (i.e., risk reduction and prevention), disaster response, and post-disaster recovery efforts. Viewed holistically, this cyclical process is made up of interconnected, interdependent stages as opposed to disjointed, independent phases. Embracing principles of resilience and disaster risk reduction, contemporary approaches involve identifying the potential risks posed by natural and technological hazards followed by the implementation of preemptive strategies before disasters even occur.

The majority of these initiatives harness the technological resources available to them. Advances in observational and telecommunication satellites, drone technology, and other technological devices help expedite relief efforts and avoid redundancy. Currently, Türkiye operates eight active satellites in orbit around the earth, five of which are dedicated to telecommunications and three to observations. Risk assessment analyses make use of appropriate satellite images to enhance their depth and scope. For instance, rapid damage assessment following an earthquake is made more robust through the use of high-resolution satellite images. Considering their role in shaping effective disaster plans and intervention mechanisms, the importance of these technologies became ever more evident following the Türkiye–Syria earthquakes.

Three separate earthquakes occurred along the Eastern Anatolian Fault during the month of February 2023. The initial two struck the province of Kahramanmaraş. The first, registering Mw 7.7, struck the district of Pazarcık at 4:17 a.m. local time on Monday, 6 February and the second, registering Mw 7.6, struck the district of Elbistan at 1:24 p.m on the same day. The third earthquake, measuring Mw 6.4, struck the district of Yayladağ, Hatay approximately two weeks later on 20 February at 8:04 p.m. The devastation wrought by these earthquakes was greatly amplified by the proliferation of buildings highly susceptible to seismic activity and ground conditions that exacerbated ground motion. In the forthcoming sections of this chapter, I will analyze the myriad efforts undertaken by Eskişehir Technical University (henceforth ESTU) personnel deployed to Elbistan’s Disaster Coordination Center (henceforth DCC) in the two weeks immediately following the two initial earthquakes that rocked Kahramanmaraş and the surrounding provinces.

Figure 1 illustrates several critical steps necessary for the disaster management loop to be successful. As depicted, completing an impact analysis and mapping of the degree damage incurred are, collectively, the foremost step to be taken.

When conditions restrict intervention capacity, it is of paramount importance that all available human and material resources be wielded as judiciously as possible. To ensure that this happens, a triage is performed during all phases of an intervention. Given that time is of the essence, the search for and rescue of injured people trapped under the rubble of completely or partially destroyed buildings is the first act to be undertaken. Disaster coordination centers are expected to assess the conditions on the ground expediently and without undue delay. Response teams in Türkiye’s Disaster Response Plan (Türkiye Afet Müdahale Planı [TAMP]) are tasked with carrying out their duties under prevailing conditions, irrespective of their constraints, from the onset of the disaster.

Immediately following the disaster, ESTU mobilized its resources and expertise to commence intervention efforts in accordance to its Directive on Disaster and Emergency Management. Accordingly, ESTU formed a team composed of seven members from the Hasan Polatkan Aircraft Rescue and Fire Fighting Unit and from the university’s various departments. Departing from ESTU’s İki Eylül Campus with one fire truck and minibus at 11:00 a.m. on Monday, 6 February 2023, this team was to report to the two-person disaster management unit headed by Dr. Muammer Tün, an associate professor at ESTU’s Earth and Space Sciences Institute and Department of Earthquake Engineering.

Upon arrival at Elbistan’s DCC, the ESTU Search and Rescue Team reported directly to AFAD for duty. Observers identified several hiccups during the intervention phase. The DCC experienced several major issues while registering arriving search and rescue teams and directing them to debris sites. They further noted a pervasive lack of coordination between bodies responsible for assigning duties to these teams and monitoring their progress in real time. The single most critical shortcoming, however, was the absence of any effort to ascertain the precise number and locations of collapsed buildings.

The DCC ESTU Search and Rescue Team found that the ground floor of the specific disaster site to which it had been assigned to work had completely collapsed in on itself. People huddled around the disaster site stated that although several of their loved ones were trapped under the rubble, they were unable to reach them because of a lack of heavy machinery. Damaged telephone lines and communications infrastructure prevented the team from contacting the DCC to request the necessary equipment to initiate search and rescue operations. Meanwhile, other individuals, themselves with loved ones trapped alive under rubble, conveyed that rescue efforts had begun without the aid of heavy machinery at another disaster site, prompting the team to relocate to that location. Despite team’s consistent efforts to keep the DCC abreast of the conditions and developments on the ground, they were unable to establish communications with the center.

Field observations noted communication breakdowns between search and rescue teams and the DCC that not only caused confusion regarding the whereabouts of each team and the severity of injuries sustained by people extracted from under the rubble but also impeded the efficient reassignment of teams to alternative disaster sites. Field conditions further complicated the relay of other critical information, including the precise number of buildings that had collapsed in Elbistan’s central districts, in which areas collapsed buildings were concentrated, the number of people requiring rescue at each disaster site, the location of each team, and the identities of those rescued from each site.

In order to expedite search and rescue operations, it was imperative that teams had access to accurate digital maps of the buildings that had been destroyed or suffered damage. Yet, as they lacked the resources to complete these tasks, the ESTU Search and Rescue Team informed the governor in charge of coordinating Elbistan’s DCC of the situation and their needs.

Upon this request, authorities promptly established a Geography Information Systems and Mapping Office within Elbistan’s DCC, furnishing it with computers, printers, and other necessarily equipment in addition to a hearty supply of consumable goods. With that, Elbistan’s Directorate of Land Management obtained the cadastral surveys of the city and, together with municipality staff, began digitally mapping the area. With access to highly detailed digital maps all located in a single centralized location, decision-makers were better equipped to manage the chaotic situation in front of them. These maps included the number of collapsed buildings, building codes, geographic coordinates, block-lot information, resident counts, building heights, construction years, and architectural blueprints.

On the second day of the disaster, Elbistan’s Police Headquarters provided the DCC a list of collapsed buildings categorized by neighborhood within the city’s central districts that its staff had compiled. Of the 500 total residences destroyed, Elbistan’s Kümbet neighborhood bore the brunt of the devastation, with 130 residences wiped off the face of the proverbial map. Still, it was necessary to verify these findings and, once confirmed, produce digital maps before coordinated operations could commence. Accordingly, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) equipped with long-range sensors were deployed over the area to identify which buildings had indeed been destroyed, as this would expedite search and rescue operations. The coordinated efforts of the Ministry of Environment, Urbanisation and Climate Change, the Directorate General of Geographic Information Systems team, and the UAV team operating under the Ministry of Defense’s General Directorate of Mapping produced a series of high-resolution aerial photographs of the city center. An application was submitted to the TÜBİTAK 1002-C Emergency Support Program for Field Studies on Natural Disasters seeking funding to use high-resolution aerial photographs and ground area scanning to pinpoint collapsed buildings, which was promptly accepted. Unfortunately, however, the aforementioned aerial photographs proved to be of no avail, as twenty centimeters (~8 inches) of snow had fallen after the initial earthquakes, effectively camouflaging the buildings that lay underneath. As a result, ESTU’s volunteer team set out in vehicles dispatched by the governor of Eskişehir on Thursday, 9 February 2023 to take photographs of all the completely and partially destroyed buildings, as well as those that had sustained severe damage, throughout the fourteen neighborhoods making up Elbistan’s urban center. The buildings in these photographs were then correlated with their respective block-lot numbers and geographic coordinates. It cannot be understated how significantly the inability to use digital maps during search and rescue operations hindered teams’ otherwise heroic efforts to remove debris and rescue survivors.

The ESTU, Gebze Technical University, and AFAD teams continued working to match the buildings with their geographic coordinates until Sunday, 12 February 2023. This same day they began submitting neighborhood-based reports to the chief prosecutor responsible for overseeing legal procedures in Elbistan.

On the seventh day following the initial earthquakes, statistical reports were published for the neighborhoods of Elbistan that had incurred the highest number of damaged buildings. Specifically, Güneşli recorded 251 completely or partially destroyed buildings, Ceyhan recorded 129, and Kümbet recorded 122. The resulting maps were a major game changer at the DCC. They expedited assessments of the extent of the earthquake’s destructive impact, facilitated legal procedures, accelerated debris removal, and streamlined the creation of damage-assessment reports by the treasury.

As we conclude our analysis of Elbistan’s response during the first week of the earthquake, the following points must be duly considered:

- It is crucial that the Disaster Information Management, Assessment, and Monitoring Group provide authorized users with 1/1000-scale digital disaster impact maps that are compatible with Türkiye’s National Geographic Information System, alongside smart city data layers, within the first twenty-four hours of a disaster.

- Since the use of digital maps that contain real-time data enhances response effectiveness, it is imperative that geographic information systems and remote sensing solution techniques be improved upon, such as by incorporating real-time offline and online server services, and made more widespread.

- Real-time images collected by unmanned aerial vehicles and satellites should be made readily available to all authorized individuals. Local personnel should be trained in how to process, analyze, assess, and interpret this data using the latest software and hardware.

- Decision-makers should be made aware of the importance of developing and leveraged to implement resilient city and community strategies that prioritize disaster risk management.

- Comprehensive policies should be formulated to address both immediate and long-term outcomes. These include restricting the development of areas prone to earthquakes, enforcing regulations that prohibit the construction of earthquake-vulnerable buildings, fostering community resilience through crowd sourcing, and identifying vulnerable social groups.

- A stronger focus should be placed on developing crowd sourced systems that can be utilized in disaster risk management and crisis response. Awareness at the local level should be increased and multidisciplinary capacity-building efforts should be integrated into resilient city and community strategies.

1 AFAD (2023). 06 Şubat 2023 Pazarcık-Elbistan Kahramanmaraş (Mw: 7.7– Mw: 7.6) Depremleri Raporu, Deprem Dairesi Başkanlığı https://deprem.afad.gov.tr/assets/pdf/Kahramanmara%C5%9F%20Depremi%20%20Raporu_02.06.2023.pdf